No products in the cart.

Blog

The Grateful Dead’s Long, Strange Trip: A History of the Legendary Jam Band

More than just a band, the Grateful Dead was a phenomenon. For three decades, they cultivated a unique blend of rock, folk, country, blues, jazz, and psychedelic improvisation that defied easy categorization. They built a loyal, sprawling community known as the Deadheads, who followed them across the country, creating a subculture centered around music, freedom, and shared experience. Their history is a fascinating saga of musical exploration, countercultural ideals, and an unparalleled connection between artists and audience.

This is the story of the Grateful Dead’s long, strange trip.

Humble Beginnings in the California Crucible (1965-1966)

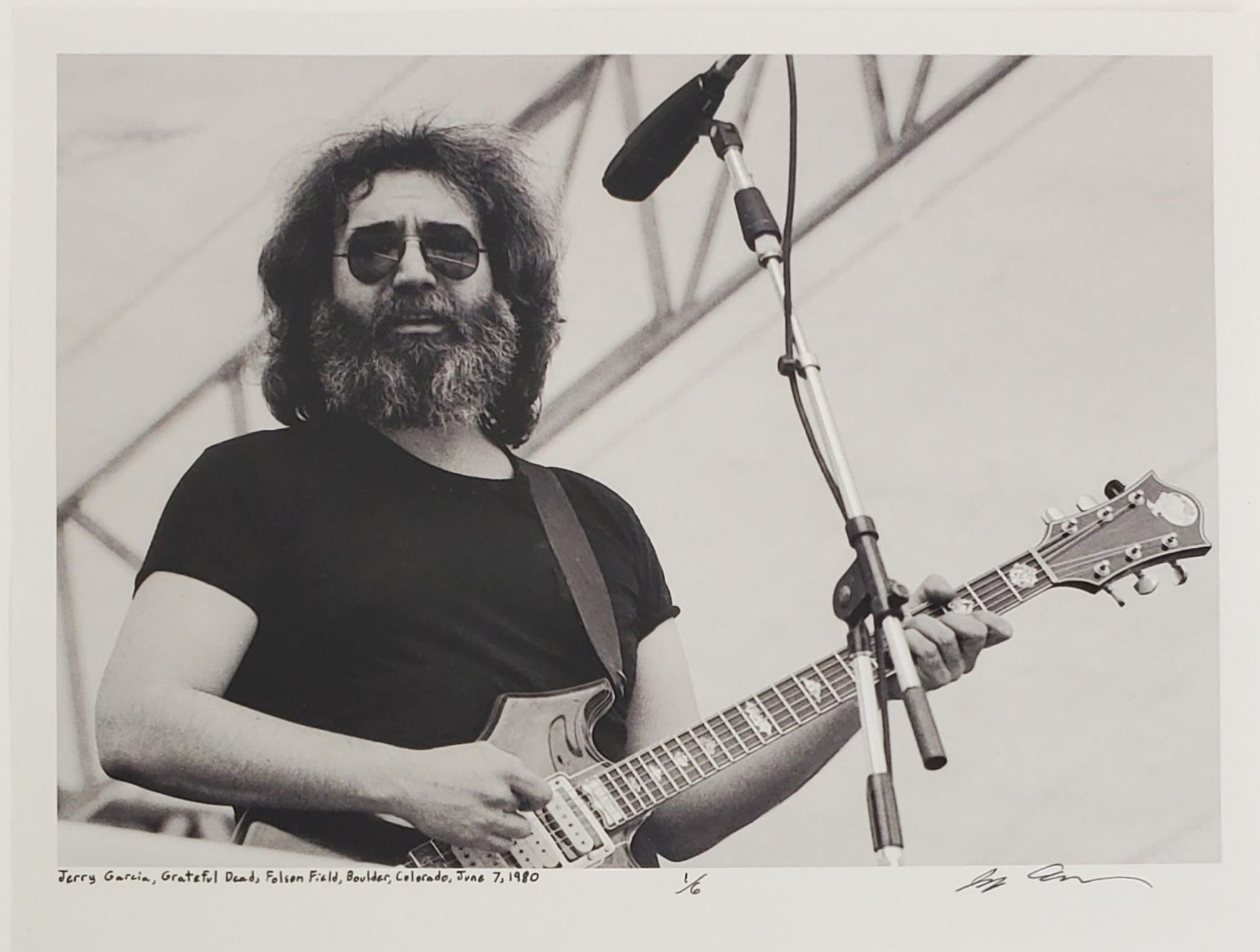

The roots of the Grateful Dead can be traced back to Palo Alto, California, in the early 1960s. Jerry Garcia, a banjo player turned guitarist with a deep love for folk and bluegrass, was a central figure in the burgeoning folk scene. He crossed paths with Robert Hunter, who would become his lifelong songwriting partner (though not a performing member of the band), as well as other musicians who would form the nucleus of the Dead.

Initially, several configurations emerged. Garcia played in a jug band called Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions with Bob Weir (guitar, vocals) and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan (keyboards, harmonica, vocals). Weir and McKernan also played in another band. The scene was fluid, and musicians often jammed together.

The real catalyst came with the advent of the Acid Tests. Organized by author Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, these events were immersive, multimedia happenings designed to explore the effects of LSD. The house band for the Acid Tests was initially called the Warlocks. This lineup solidified around Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, Phil Lesh (bass), and Bill Kreutzmann (drums). Lesh, originally a trumpet player with a background in avant-garde classical music, brought a unique, melodic approach to the bass that was foundational to the Dead’s sound. Kreutzmann’s rhythmic dexterity provided the backbone.

Performing at the Acid Tests exposed the band to chaotic, free-form environments where improvisation wasn’t just encouraged – it was necessary. They learned to stretch songs, explore musical ideas on the fly, and react to whatever the environment threw at them. This crucible forged their identity as an improvisational live band.

The name change from Warlocks to the Grateful Dead is shrouded in legend. The most commonly accepted story involves the band opening a dictionary or folklore text to find the term “grateful dead,” which refers to a folk motif about a deceased person’s spirit aiding someone who paid their debts or arranged their burial. Regardless of the exact origin, the name stuck, evoking a sense of history, mystery, and perhaps a touch of the macabre that fit the psychedelic era.

The Psychedelic Explorations and Early Albums (1967-1969)

Signed to Warner Bros. Records, the Grateful Dead released their self-titled debut album in 1967. It was a mix of R&B covers (reflecting Pigpen’s influence) and original material, recorded relatively quickly. While it captured some of their energy, it struggled to translate the expansive, improvisational nature of their live shows into the studio format.

Their second album, Anthem of the Sun (1968), was a bold attempt to fuse studio recordings with live performance snippets and experimental techniques. It was a sonically ambitious, collage-like work that better represented their psychedelic explorations but was challenging for many listeners.

Aoxomoxoa (1969) continued this experimental studio approach. Both Anthem and Aoxomoxoa were expensive to produce and didn’t yield commercial hits, leaving the band in debt to the label. During this period, they also added a second drummer, Mickey Hart, whose background in percussion and rhythm added another layer of complexity to their sound, creating the signature “drumz” and “space” segments of their live shows.

These early years were characterized by deep dives into psychedelic rock, long instrumental passages, and a willingness to push musical boundaries. They were part of the vibrant San Francisco scene alongside bands like Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Santana, performing frequently at venues like the Fillmore and Avalon Ballroom.

Finding Their Voice: Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty (1970)

Facing financial pressure and perhaps a natural evolution of their songwriting, 1970 marked a significant turning point with the release of two albums that would become cornerstones of their catalog and define a crucial part of their sound: Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty.

Moving away from the studio experimentation of the previous albums, these records embraced simpler, more acoustic arrangements and showcased the brilliant songwriting partnership between Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter. Hunter’s lyrics, filled with American archetypes, historical allusions, and philosophical musings, combined with Garcia’s melodic sensibilities, created songs that felt both timeless and deeply personal.

Workingman’s Dead featured tracks like “Uncle John’s Band,” “Casey Jones,” and “High Time,” incorporating elements of folk, country, and blues. American Beauty followed later the same year, offering classics such as “Box of Rain,” “Friend of the Devil,” “Sugar Magnolia,” “Ripple,” and “Truckin’.” These albums were more commercially successful than their predecessors and solidified their reputation as gifted songwriters, not just improvisational musicians.

These albums also cemented the vocal contributions of the other members. Weir’s catchy, rock-and-roll flavored songs like “Sugar Magnolia,” Lesh’s rare but powerful lead vocals on tracks like “Box of Rain,” and Pigpen’s soulful blues numbers provided crucial variety.

The Road Warriors and the Rise of the Deadheads (The 1970s)

With a growing repertoire of strong songs and their live reputation preceding them, the Grateful Dead became first and foremost a touring band in the 1970s. They played hundreds of shows each year, developing an almost telepathic communication on stage that allowed for truly spontaneous improvisation. No two shows were ever the same. Setlists varied wildly, and songs could stretch into lengthy, exploratory jams.

This dedication to live performance and musical spontaneity fostered a unique relationship with their audience. Fans began following the band from city to city, recording shows (with the band’s blessing, a revolutionary concept at the time), trading tapes, and building a network around the shared experience. This was the birth of the Deadhead community.

The band actively encouraged tapers, setting up dedicated sections for them and even providing a feed from the soundboard. This policy, driven by the philosophy that the music belonged to the fans once it was played, created a vast, decentralized archive of their live performances and fueled the growth of their fanbase through word-of-mouth and tape trading.

Key developments in the 70s included:

The “Wall of Sound”: A massive, complex, and innovative sound system designed by their sound engineer Owsley “Bear” Stanley, aiming for high fidelity and even sound distribution. It was logistically challenging and expensive but iconic.

Personnel changes: Pigpen’s health declined, leading to his death in 1973. Pianist Keith Godchaux and his wife, vocalist Donna Jean Godchaux, joined the band, adding a new dynamic.

The 70s were the era where the Grateful Dead perfected their live craft, blending tight arrangements with fearless improvisation, and solidifying the itinerant culture that surrounded them. The music wasn’t just happening on stage; it was happening among the fans in the parking lots (Shakedown Street) and in the shared energy of the shows.

Navigating the 80s and Unexpected Mainstream Success

The 1980s presented new challenges and opportunities. The band’s grueling touring schedule took a toll, and members struggled with health issues and substance abuse, particularly Jerry Garcia. Musically, they continued to evolve, adding Brent Mydland on keyboards and vocals in 1979 after the Godchauxs departed. Mydland brought a dynamic energy, strong vocals, and songwriting contributions that revitalized the band’s sound in the 80s.

Despite being known primarily as a live act with a dedicated cult following, the Grateful Dead achieved unexpected mainstream success in 1987 with the album In the Dark and the hit single “Touch of Grey.” The song’s catchy melody and resilient lyrics (“I will survive”) resonated with a wider audience, sending the album to number 6 on the Billboard charts and giving them their first and only Top 10 hit.

This sudden surge in popularity, often referred to as the “Touch of Grey phenomenon,” brought a massive influx of new, younger fans (“Touchheads” or “New Dead”) to their shows. While it expanded their reach, it also sometimes clashed with the older, established Deadhead culture and presented logistical challenges for the band and venues dealing with unprecedented crowd sizes.

Tragedy struck in 1990 with the death of Brent Mydland from a drug overdose. His passing was a significant blow. The band continued with Vince Welnick on keyboards and Bruce Hornsby occasionally joining.

The End of an Era and Lasting Legacy (1990s onwards)

By the early 1990s, Jerry Garcia’s health was in serious decline, exacerbated by years of drug use. The band continued to tour, but the energy and spontaneity that defined them were sometimes less consistent.

The long strange trip of the Grateful Dead as a touring unit with Jerry Garcia at its helm came to an end with his death on August 9, 1995, at the age of 53. Garcia was the spiritual and musical heart of the band, and his passing marked an undeniable conclusion to that chapter. The remaining members decided not to continue performing as the Grateful Dead without him.

However, the music and the community were far from dead.

The legacy of the Grateful Dead is vast and multifaceted:

Musical Influence: They pioneered the jam band genre and influenced countless musicians across various styles, from rock and jazz to bluegrass and experimental music. Their approach to improvisation, setlist variation, and live performance remains a benchmark.

The Deadhead Community: The bond between the band and its fans is legendary. The Deadheads are one of the most dedicated and well-documented fan bases in music history, characterized by their nomadic lifestyle following tours, their tape-trading culture, and a shared sense of identity and belonging.

Archival Releases: The band’s commitment to recording their live shows resulted in a massive archive. The series of official live releases (Dick’s Picks, Dave’s Picks, etc.) continues to provide fans with high-quality recordings of iconic performances, ensuring the music lives on.

Continuing the Music: The surviving members have continued to perform the Grateful Dead’s music in various configurations, such as The Other Ones, The Dead, Furthur, Phil Lesh & Friends, and most notably, Dead & Company (featuring Weir, Hart, and Kreutzmann alongside John Mayer and others). These projects keep the music alive for older fans and introduce it to new generations.

Business Innovation: The Grateful Dead were pioneers in areas like direct-to-fan marketing, allowing taping, and building a relationship with their audience that bypassed traditional music industry gatekeepers.

The Grateful Dead’s journey was messy, unconventional, and sometimes challenging, but it was undeniably authentic. They were musicians who prioritized the live experience, who built a family around their sound, and who created a body of work that continues to inspire loyalty and discovery decades after their initial run ended.

Their story is a testament to the power of improvisation, the strength of community, and the enduring magic of a long, strange trip lived fully and loudly. The music plays on, and the legend of the legendary wanderers continues.